Bayleaf is a timber-framed hall-house dating mainly from the early 15th century. The central hall, heated by an open fire, is flanked at one end by service rooms and at the other by rooms for the owner and his family.

With replica furniture and equipment, the farmstead is presented as it might have been in about 1540. Most Wealden houses were built in a single operation, but Bayleaf appears to have been built in two separate stages.

In the first phase, which has been dated to about 1405–30, the open hall and the service end of the building were probably attached to an earlier structure, which stood where the solar end bay now stands.

Some time later this earlier structure must have been removed and the solar end bay built in its place, giving the building its present form.

Share

Overview

Dates From

1405–30 & 1480–1520

Dismantled

1968

Reconstructed

1972

Original Location

Chiddingstone, Kent

Building History

The Open Hall

The open hall is of two bays. Its floor area is not large but its height and proportions create a sense of grandeur — the central open roof truss is an important feature of halls such as this. Visitors with an eye for symmetry will notice that the crown posts in the centre of the roof trusses are not central to the width of the hall itself, because the roof extends two feet outside the recessed front wall.

Interior of Bayleaf Farmstead showing hearth/open hearth and main hall.

The tie beam is supported by two massive arch braces. The original braces had been removed to create more space upstairs when the hall was floored over in the late 16th century, so new ones had to be found for the Museum reconstruction. They are each thirteen feet long and weigh nearly four hundredweight, and were cut from a tree which had grown with a suitable curve.

The position of the hearth in the open hall is conjectural, but is based on the evidence of hearths discovered by archaeologists in similar houses. The smoke from the fire may have escaped originally through the triangular gablet at the service end of the house, this being the usual arrangement in other hall-houses with hipped roofs, or through apertures formed in the ridge of the roof. In practice most of the smoke seeps out through gaps between the roof tiles.

There was evidence in the rafters that a louvre had been built on the roof at the service end of the hall, but this was possibly an intermediate stage of improvement prior to the insertion of the brick chimney stack in 1636, rather than part of the original open hall.

The main pieces of furniture in the hall are the table, laid with a cloth, and the cupboard, on which pewter is displayed. This reflects the wording of probate inventories of the period, which often contain an entry such as: ‘In the hall, one table and a form, three stools, one cupboard…’

Parlour & Solar

Beyond the hall are the two rooms traditionally known as the parlour and solar. The solar — the upper chamber — was probably used as the family’s private bed-sitting room. It is dominated by a high quality arch-braced tie beam, and has its own privy, suggesting that it was considered the most important private room in the house.

The tie beam in this room is a particularly interesting feature. Instead of running across the building, as it normally would, it is parallel with the line of the roof, changing the axis of the chamber and giving it the dignity of a two-bay cross wing.

The window shutters in the solar slide vertically in grooves cut into the timbers. Normally medieval window shutters were either hinged, like those in the hall, or were designed to slide horizontally.

The reconstruction of the privy is partly conjectural, being based on mortices in the main timbers of the wall and on other surviving privies. It is not clear whether it originally emptied straight into an open cess-pit or whether there may have been some kind of covered conduit, but the contents were used as garden manure. Another privy would have stood outside the house.

Service Rooms

Below the passage, at the other end of the hall, are the service rooms, traditionally known as the buttery and pantry. The buttery seems to have been used mainly for storing vessels and utensils, while food, especially flour, was stored in the pantry.

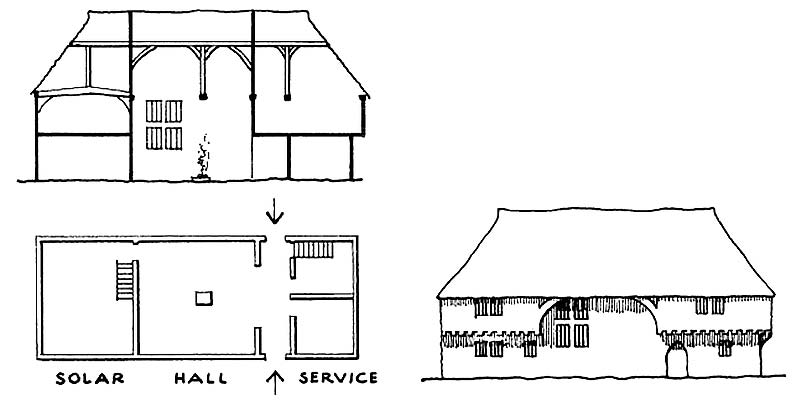

Cutaway drawing of Bayleaf showing structure and plan.

Some cooking may have taken place on the fire in the hall, but by the mid 16th century most houses of this size in Kent also had a kitchen — in many cases detached from the house for fire safety — which was used for baking and brewing.

A medieval illustration showing a garderobe projecting from the wall of a house, with a cesspit below. The unfortunate person in the cesspit has fallen through a broken floorboard. From a 15th century French translation of Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Wealden House

Bayleaf is an example of a type of house which is common in south-eastern England, and particularly in the Weald of East Sussex and Kent — hence the name ‘Wealden’ house. Its characteristic feature is the recessed front wall of the hall.

The two end chambers are both jettied out at the front of the building but the hall has no upper floor and no jetty, and the upper part of the front wall is therefore recessed. Most of these houses were built by prosperous traders and craftsmen in towns, and by yeoman farmers in the countryside.

Bayleaf Wealden House

The entrance door opens into a cross passage, which is divided from the hall by short screens at either side of a wide opening. The open hall is of two bays, the ‘lower’ bay and the ‘upper’ bay.

The lower bay has no windows, while in the upper bay double-height windows throw light on the high table — in the centre of which would have sat the head of the household. The fire on the open hearth produces smoke which deposits a thick layer of encrusted soot on the beams.

A doorway by the high table leads to the ‘solar’ end of the house. The upper room, traditionally known as the solar, probably provided the family’s private bed-sitting room, while the lower room (which became known as the parlour) may have been used variously for sleeping, storage and working.

At the lower end of the hall are two service doorways with arched heads, opening into the two service rooms — traditionally called the buttery and pantry. These rooms were for storing food, vessels and utensils. A third doorway at the back of the house opens onto stairs leading to the service chamber.

Bayleaf Garden, Orchard & Shaws

Since 1987 the Museum has undertaken the creation of features in the curtilage and landscape around Bayleaf, with the intention that the immediate surroundings of the house will eventually have the character, and in many respects the detail, of its original setting in the early 16th century.

Bayleaf’s garden

The Garden & Orchard

Medieval pictures and documents tell us much about contemporary gardens, but very few of them refer to the gardens of rural farmhouses such as Bayleaf. It seems likely, however, that Bayleaf’s garden would have been largely devoted to vegetables, fruit and herbs for use in the household.

The vegetables were mainly brassicas such as cabbages and turnips, with leeks or onions, peas and beans, lettuce, and spinach beet. Many of the greens would have been used for boiled pottage or soup.

A wide variety of herbs were grown, and there would probably have been gooseberries, raspberries and wild strawberries in addition to hedgerow fruit such as blackberries, crab apples, plums and damsons. The orchard contains apple and pear trees. The research for the Bayleaf garden was carried out by Dr Sylvia Landsberg, and the garden was created by R Holman.

The Shaws

A shaw is the name given to small woodlands found in the Weald of Kent, Sussex and Surrey. They are usually long and narrow, and lie along a field border. They are believed to be the remains of primeval woodland, left when fields were first reclaimed from the Wealden forest, but maintained and developed with later planting.

Their true purpose is unknown, but it is clear that they provided shelter for stock in the fields, and that they were intensively managed to produce both timber and underwood. Since the 18th century shaws have been gradually removed to give bigger fields and narrower hedges, but many still exist and are now being closely studied to discover their history and purpose.

Many shaws existed in the vicinity of Bayleaf in its original location in Kent, and at the Museum three areas have been planted with appropriate trees and shrubs. Two of them are based on the shaws closest to Bayleaf’s original site, known as Bayleaf Shaw and Batfold Shaw, and the third contains common species found in other Wealden shaws.

Oak and ash are the main timber trees, and other species include hazel, hawthorn and field maple. In years to come, when they have matured and developed, the shaws will give an authentic picture of the wooded landscape of the original Bayleaf area. Research on this and other aspects of the Bayleaf project was carried out by Environmental Historian Ruth Tittensor.

Late Medieval Rural Life

The below manuscript illustration was made in the late 15th century and shows a range of rural activities. It is from a French version of the early 14th-century ‘Liber ruralium commodorum’ by Pietro de’ Crescenzi. Much of our knowledge of the general character of the late medieval rural landscape comes from illustrations such as this, many of which are Flemish or French.

In the left foreground a gardener is digging a raised bed; to the left stands a wicker basket containing a plant. In the centre a lady is smelling a flower from the bunch in her right hand. To her right a man is mowing grass and behind him is a man with a basket of grapes, presumably gathered from the vine at the right of the picture.

An apple tree stands in an enclosure surrounded by a woven wattle fence, with a ladder and a basket full of apples. Behind the tree a butcher is about to slaughter an ox, which is standing with its front legs ‘hobbled’ or tied. In the centre of the picture a man is shearing a sheep. In the background can be seen a pair of oxen pulling a wheeled plough, a man cutting corn with a sickle, and a man splitting wood.

Article: Bayleaf Wealden Hall House

Bayleaf Wealden Hall House by Dr Danae Tankard

Bayleaf house reconstructed at the Museum.

Bayleaf – perhaps the most iconic building to be re-erected at the Museum – is a timber-framed Wealden hall house from Chiddingstone in Kent. It has six rooms, four on the ground floor and two upstairs.

Bayleaf on its original site at Chiddingstone, Kent.

The house was built in two phases. The earliest part, which has been dendro-dated to 1405-1430, consisted of an open hall and service end. This was probably attached to an earlier structure, which stood where the solar or upper end bay now stands. It is believed that the upper end bay that gave the building its present form was added in the early 16th century, replacing the earlier structure.

Bayleaf on its original site, before dismantling. The added rear wing has not been included in the reconstruction.

The parish of Chiddingstone, comprising about 6,000 acres and with an estimated population in the 1560s of 475, is on the western side of the Kent Weald, close to the Surrey border. The village of Chiddingstone consists of a high street and the church of St Mary. Most of the inhabitants were (and still are) scattered widely throughout the parish.

Chiddingstone straddles both low and high Weald, the original site of Bayleaf lying in the low Weald. The high and low Wealds were separated both demographically and industrially, with the high Weald more heavily populated and industrialised than the low Weald.

Bayleaf during dismantling. The solar end has been removed, leaving the original hall and service end.

Overall the Kent Weald was the poorest of Kent’s agricultural regions and within the Kent Weald the western Weald was poorer, less industrialised and more sparsely populated than the other Wealden districts, particularly the central Weald where the woollen textile industry was based.

The ‘Gentry Manor’ of Bore Place

All land in the Kent Weald, like elsewhere in England, was held of some lordship or directly of the Crown. However, seigneurial control was weak and tenants’ involvement with their manor was limited to paying a small annual quitrent or ground rent, doing (occasional) suit of court and paying a heriot (usually the best beast) for the right to take up land on the death of the previous tenant.

A feature of the late 15th and 16th centuries was the appearance of what are described as ‘gentry manors’ or estates in all parts of the Weald, the result of either successful estate building by local residents or of purchase by newcomers to the Weald. These estates frequently included land held of more than one manor. An example of this was the Bore Place ‘manor’, or estate, with lands in at least three different manors.

Bore Place.

The owners of Bore Place, like most other landowners in the Weald during this period, managed their property by leasing out large blocks of it and rents would have formed an important part of their income. Unlike some landowners, however, they retained demesne lands, which in 1518 included approximately 50 acres of arable and 150 acres of pasture, together with meadows, woods and parkland.

From the late 15th century and throughout the 16th century Bore Place was held by a succession of eminent London lawyers, all of whom continued to maintain London residences. John Alphegh held the estate until his death in 1489. He left it to his daughter, Margaret, and her husband, Robert, later Sir Robert, Rede.

On Rede’s death in 1518 the estate passed to his daughter, Bridget, and her husband, Thomas, later Sir Thomas, Willoughby. Bridget continued to hold the estate after her husband’s death in 1545 and on her own death in 1558 it passed to her grandson, Thomas Willoughby.

Bayleaf Farm

The origins and development of Bayleaf are unclear. The name ‘Bayleaf’ is a corruption of the word ‘Bailey’ and it is probable that it was named after its original occupant, Henry Bailey. We know that at the end of the 14th century Henry Bailey was holding about 100 acres of land in the area that later became Bayleaf farm and that he died in around 1430. He may therefore have been responsible for building the original house.

The earliest reference to Bayleaf (‘Bayles’) is in the will of John Alphegh dated 1489, and it thereafter appears regularly in rentals and other documents throughout the 16th century as ‘Baylys’, ‘Bailes’, ‘Bayleaze’ and ‘Baylies’.

From the early 16th century Bayleaf is described as a ‘fee farm’ and the tenants paid an annual rent of 110s. The exact acreage at this date is unknown although it is reasonable to assume on the basis of earlier and later evidence that it was somewhere in the region of 100-130 acres.

The description of the tenants as ‘farmers’ (firmarius) and the fact that they were paying a fixed rent indicates that Bayleaf was being held on a long-term lease, for a term of years or for a succession of lives (usually three – e.g. father, son, grandson). This means that the tenants were unaffected by the custom of ‘gavelkind’ which was distinctive to Kent and was characterised by partible inheritance amongst male heirs (that is, land was split equally amongst them).

The evidence for tenure of Bayleaf during the 16th century is relatively clear, although the exact dates for each tenant are not. It is likely that Thomas Wells (the first) held Bayleaf from at least 1500 to 1510, Edward Wells held Bayleaf from about 1510 to 1520, Richard Scoriar held Bayleaf from about 1520 to 1540 and Thomas Wells (the second) held Bayleaf from about 1550 to about 1590.

The exact relationship between these men is unknown: an obvious explanation would be Thomas Wells (the first) was the father of Edward Wells who was the father of Thomas Wells (the second), but other relationships are possible. Why Richard Scoriar was holding the lease is unclear: possibly it was during the minority of Thomas Wells (the second).

The only one of these men about whom anything is known is the second Thomas Wells. No wills survive for any of them, one of the most useful sources of information for men and women at this date.

Bore Place and Bayleaf map.

What Do We Know About Thomas Wells?

There is a document dated 1556 which records an agreement between Thomas Wells and Lady Bridget Willoughby, then the owner of Bore Place, in which he agrees to supply her with wheat and oats for a period of five years and to ‘bring and carry or cause to be brought and carried yearly during the space of 20 years’ from London to ‘the house of the said Lady Willoughby called Bore one sufficient wain load of such victuals and stuff as she or any other to her use shall buy and provide for the provision of her house’. In this document Thomas Wells is described as a ‘carpenter and farmer’.

Ten years later when Thomas Willoughby (the second) mortgaged Bayleaf ‘with all its lands, appurtenances, pastures and woods now in the tenure and occupation of Thomas Wells’ to Richard Water, a wealthy miller, Thomas Wells is described as a yeoman. So he was a farmer, a carpenter and, at least by 1566, a yeoman.

A yeoman is a recognised economic class in the early modern period and usually describes someone who was farming at least 100 acres. He was above ‘husbandman’ but below ‘gentleman’. In other words, yeomen constituted a rural middle class. He would expect to produce a large marketable surplus each year and be a regular employer of non-family labour.

Evidence from London, where carpenters were organized in a craft guild (the carpenters’ company) suggests that the profession was not a very profitable one. However, outside London and the larger provincial towns the activities of carpenters were unregulated which means that there are few details of how the craft was organised or of the wealth it generated.

As a carpenter Thomas Wells might have been responsible for building entire houses as well as commercial and industrial buildings. The more successful carpenters acted as architect contractors, arranging for materials and sub-contracting with other craftsmen.

Analysis of tax and poor rate assessments suggests that Thomas Wells was a wealthy man within his community – in the top 10% of the Chiddingstone population – which would have made him a substantial, and respected, member of the community. This is reflected in his local office holding.

In 1562 he was elected to the office of constable of the hundred of Somerden, an unpaid position he would have held for two years. A hundred was a unit of administration covering a number of parishes. As a constable for the hundred he (together with another constable) would have overseen the collection of poor rates, the supervision of parochial officers and the maintenance of roads and bridges. Together with petty constables they were also responsible for controlling any disturbances within their communities.

Between 1565 and 1566 Thomas Wells also served as one of two collectors of the poor, an office (later called overseers of the poor) that emerged from the developing poor law legislation of the 16th century.

Bayleaf farm comprised between 100-130 acres of land, a mixture of arable, pasture, woods and meadow. How it is farmed is unclear. In this region of Kent livestock farming – cattle rather than sheep – was predominant. Only one quarter of the demesne lands were being used for arable in the early 16th century, the remainder being pasture, even though this meant that the owners of Bore Place were obliged to buy in additional grain to supply their household.

Like Thomas Wells, they grew wheat and oats. Barley, which did not grow well on the heavy clay soils of the Weald, had to be bought in. The commercial value of cattle was in their meat and hides, with some of the cattle destined for the London market.

Bailiff’s accounts for Bore Place which survive for the years 1513-1514, 1516-1517 and 1517-1518 show that the bailiff (William Walker) was selling livestock to individual traders spread out over an approximately 40-mile radius from Chiddingstone, including to a trader from Southwark where the London tanning industry was based.

The baptism register for Chiddingstone, which begins in 1566, records the birth of five of Thomas Wells’ children within a 10-year period – three boys and two girls. By this date he already had at least one son, Thomas, which we know because there is a record of his burial in 1572. Another son, Percival, died aged two in 1571.

A ‘snapshot’ of the Wells family in December 1578 at home in Bayleaf would find Thomas and Mrs Wells, Anne aged seven, Henry aged five, Ralph aged two and Martha aged one month. There may have been one or two older children whose births pre-date the start of the baptism register and who survived to adulthood.

It is likely that the Wells’ household included at least one, and probably two, female domestic servants, so called ‘life cycle’ servants who entered service in their mid-teens and stayed until they married in their early to mid twenties. This means that the Wells’ household is likely to have been large at between nine and 10 people, considerably larger than the average early modern household of five but consistent with what is known of other Chiddingstone yeomen families at this date.

Thomas Wells must have relied on paid labour to manage his farm, probably day labourers who would have been employed on a seasonal basis. Such men are likely to have maintained their own households and so would not have been resident in Bayleaf.

It is probable that Thomas Wells was illiterate. Although unequivocal corroboration for this is missing, in 1581 only seven out of 17 jurors of the Somerden hundred court – men of the same status as Thomas Wells – were able to sign their names: the rest indicated their assent with their ‘mark’.

Had he been able to write one would expect him to have signed the 1556 agreement he entered into with Lady Bridget Willoughby, discussed above. Instead, he ‘signs’ it with his seal. Although nationally literacy levels were rising throughout the early modern period, outside of London and larger urban centres illiteracy remained the norm below the ranks of gentry.

Bailiffs for Bore Place?

The question of whether or not the occupants of Bayleaf were literate takes on more significance when we consider the evidence for whether or not they were bailiffs. The link between the occupants of Bayleaf and the office of the bailiff derives in the first instance from the belief that ‘Bayleaf’ is a corruption of the word ‘bailiff’.

However, as we have seen, it is more likely that Bayleaf took its name from the original occupant, who was probably Henry Bailey. Whilst the surname ‘Bailey’ derives from the office of bailiff, by the 15th century the link between the occupation and the surname had become historic. Weight has been added to the Bayleaf/bailiff association by the reference in Lady Bridget Willoughby’s will of 1556 to ‘William Wells my bailiff’.

Who William Wells was and his relation to the tenants of Bayleaf is unclear. His name does not appear in contemporary tax records for Chiddingstone or the adjacent communities, which may indicate that he fell below the tax threshold or that his status as a dependent servant exempted him.

Whilst it is reasonable to assume he was related to Edward or Thomas Wells, he may have been part of their wider kin network, resident either in Chiddingstone or its environs.

We do know that between 1513 and 1518 the Bore Place bailiff was a man called William Walker, who had no connection with Bayleaf. In his will of 1519 Sir Robert Rede left Walker a tenement called ‘Mayes’ in the neighbouring village of Sundridge, and it is likely that this is where Walker lived during Rede’s lifetime.

Select Bibliography

- G Jones, ‘The Bough Beech Buildings’ (report commissioned by the Weald & Downland Open Air Museum, 2000)

- J Munby, ‘Wood’ in J Blair & Nigel Ramsey (eds), English Medieval Industries (London, 1991), 379-405

- M Zell, Industry in the Countryside: Wealden Society in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge, 1994)

Top 3 Interesting Facts

‘Wealden’ Hall House

Bayleaf is an example of a type of house which is common in south-eastern England, particularly the Weald of East Sussex and Kent.

Bayleaf Farmstead

The whole of the Tudor farmstead, including detached kitchen, Cowfold barn, garden and orchard together give context to the farmhouse.

Upstairs Privy

The upstairs privy may have originally emptied straight into an open cess-pit below and the contents used as garden manure!